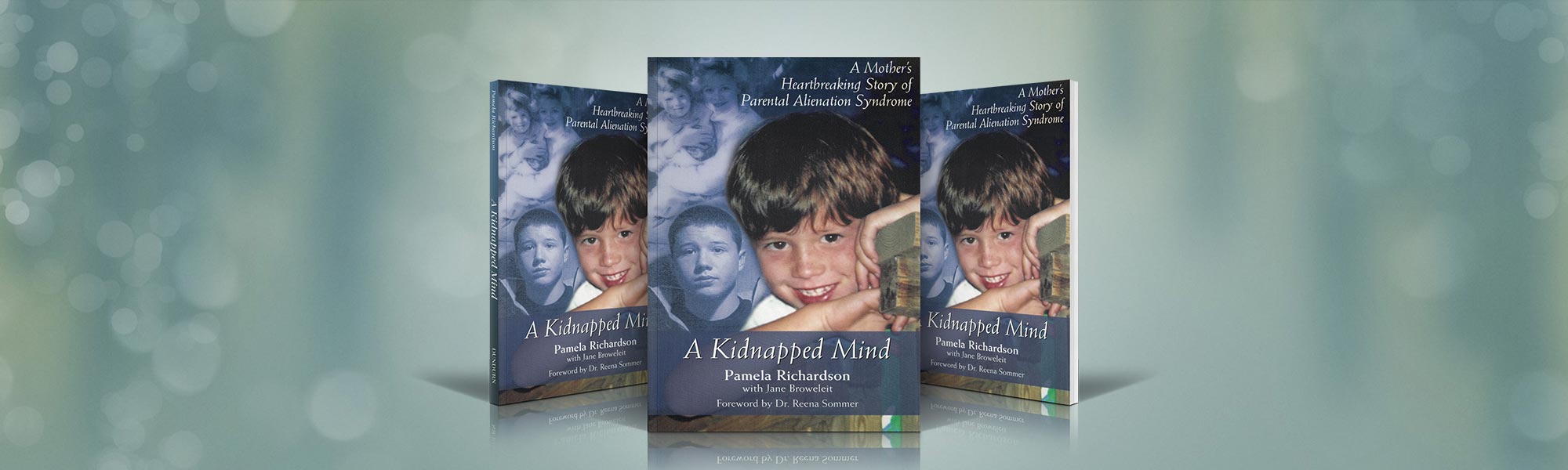

About the Book

About author Pamela Richardson

Pamela Richardson was born in Montreal, Quebec and grew up in Vancouver, British Columbia when her family relocated in the 1950’s.

Pamela Richardson was born in Montreal, Quebec and grew up in Vancouver, British Columbia when her family relocated in the 1950’s.

During her student years at the University of British Columbia she worked part time as the assistant fashion coordinator for The Hudson’s Bay Company, this lead to a full time position as Regional Fashion Coordinator for the 12 HBC stores in British Columbia.

In 1972 she moved to London, England and was a set and wardrobe stylist for television commercials and feature films. Pamela returned to Vancouver and the position of Regional Fashion Coordinator for The Hudson’s Bay and Sears stores.

In the early 80’s Pamela began her career as a journalist and on-air personality at CKVU. She had her own magazine format weekly television program called The Saturday Show which covered everything that was going on in the city culturally and artistically.

After retiring from television Pamela continued her career as the Special Events Coordinator for Vancouver Magazine and Western Living and was the west coast representative of Toronto Life fashion magazine.

Today Pamela and her husband Dave continue to live in Vancouver where their main focus is on a number of philanthropic enterprises. They have two sons Colby and Quinten, both who were on Men’s Crew and recent graduates of Brown University.

Why Parental Alienation Syndrome?

What does Parental Alienation Syndrome mean? In my case, it meant losing a child. When Dash was 4 1/2 years old his father and I broke up. I dealt with the death of our marriage and moved on but Peter stayed angry, eventually turning it toward his own house, teaching our son, day by day, bit by bit, to reject me.

What does Parental Alienation Syndrome mean? In my case, it meant losing a child. When Dash was 4 1/2 years old his father and I broke up. I dealt with the death of our marriage and moved on but Peter stayed angry, eventually turning it toward his own house, teaching our son, day by day, bit by bit, to reject me.

Parental Alienation Syndrome typically means one parent’s pathological hatred, the other’s passivity and a child used as a weapon of war. When Dash’s wonderful raw materials were taken and shaken and melted down, he was recast as a foot soldier in a war against me.

Abraham Lincoln said, “Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.” Within weeks of his first court win, Peter, a lawyer, had me removed from my volunteer work as Mother’s Help in Dash’s kindergarten. I took the issue to court but lost. Peter had been named custodial parent, by the barest of margins, and now he made the rules. He banned me from contact with Dash’s doctor or dentist.

I couldn’t attend the twice-yearly parent-teacher nights, and because I didn’t receive any of Dash’s report cards, I missed the ones that, within a couple of years, began to spell trouble.

I didn’t know about Dash’s school sports days or soccer games unless another mom told me. When Dash and I spoke on the phone our calls were monitored. Dash was rewarded if they went badly – if he was sullen or, better still, rude or difficult.

Losing Dash

Despite having an access order for 50% of Dash’s time, I soon went months without seeing him. Dash put up what resistance he could, and when I drove over each week to pick him up, if he was alone at home he would run outside to greet me, jumping right in the car for a blissful couple of hours with me. He’d sit close, not letting me out of his sight. He could be programmed to reject me, but not to hate me. I was his mom.

Despite having an access order for 50% of Dash’s time, I soon went months without seeing him. Dash put up what resistance he could, and when I drove over each week to pick him up, if he was alone at home he would run outside to greet me, jumping right in the car for a blissful couple of hours with me. He’d sit close, not letting me out of his sight. He could be programmed to reject me, but not to hate me. I was his mom.

It wasn’t long before he slid, however. At first he was emotional and aggressive but then he just shut down. He couldn’t cope with anything. His teachers saw it, his friends walled themselves off, parents who didn’t even know me asked, “Is your son OK?”

I watched, listened and triaged his pain whenever I saw him. I documented the missed access, the blocked calls and the lies Dash had learned to repeat.

Time and again I went to the courts and showed them Dash’s trauma – the eight-year-old boy who cried, “I have a bad life”, the nine-year-old boy who wanted to jump out a three-storey window and the twelve-year-old boy who wore his father’s clothes to court.

The provincial government appointed a child advocate who said: “Dash’s memories have been augmented.” Still, my ability to help Dash remained marginal. There was a sliver of hope, a slice of help, but no support from the courts. The judges wouldn’t enforce the access order and none of them stood up to Peter.

My Last Gift

I spent a quarter of a million dollars and twelve years in court, at first trying just to see him and then trying to get him help, so I never had the time to break down. I didn’t even have time to get mad. From the margins of Dash’s life I roused those who were in a position to help him.

I spent a quarter of a million dollars and twelve years in court, at first trying just to see him and then trying to get him help, so I never had the time to break down. I didn’t even have time to get mad. From the margins of Dash’s life I roused those who were in a position to help him.

A Kidnapped Mind is the story of our struggle, the hope, the missteps and all the agonizing drama along the way. I fought for Dash every day of his life, knowing in my heart that I could still make a difference.

I wrote this book as the last gift to my wonderful, brave, brown-eyed son, Dash. All profits from this book go to The Dash Foundation, formed by my husband and I to increase awareness of the damage done by this insidious and oftentimes invisible form of child abuse.